Online ads account for a staggering amount of the data that our browsers consume. They increase load times by an average of five seconds per page viewed on a mobile phone. By some accounts, downloading ads and trackers costs the average user up to $23 per month in data fees alone.

Behind the scenes, ad exchanges like AppNexus and Google DoubleClick suck up and analyze personal information from users’ online behavior, such as browsing history, device information and location data. These data can often be combined with identifying personal information like email addresses and Facebook account IDs to build a terrifyingly complex profile of a user. User data are often sold and resold, sometimes to companies not even in the business of advertising online.

Unsurprisingly, users are increasingly turning to ad and tracker-blocking software like AdBlock and Privacy Badger. This hurts publishers, who don’t receive payment from ad exchanges if their page loads without ads. Publishers retaliate by setting up ad-blocker-blockers, forcing users to whitelist their site in order to access its content. Worse yet, some providers of ad-blocker software will whitelist sites for users in exchange for money, making them de facto gatekeepers of what ads a user does and doesn’t see.

The situation isn’t much better for advertisers, either. Digital advertising fraud costs marketers and advertisers billions of dollars a year, as scammers use botnets and click farms to inflate traffic figures and charge for ad impressions that are never seen by real customers. There’s little impetus to combat this fraud from the ad exchanges, who make just as much money from fraudulent impressions as genuine ones.

The world of online advertising is a mess. It’s a bad deal for users, advertisers and publishers. And the only reason this broken system still exists is because historically it’s the only way that publishers have been able to remain solvent.

All this is not to say that alternatives have not been tried. Paywalls, usually broached out of desperation by beleaguered newspapers, are seen as the primary means by which to bolster or replace revenue from ads. While paywalling does at least ensure that readers pay for what they read, ad-blocker or no, it can discourage new readers and frustrate existing ones who browse the web on an ever growing number of devices. Frustratingly, paywalled content is often served with ads anyway.

Recently, a third revenue stream has proved an unlikely success for some online publishers: voluntary donations from users. In 2014, The Guardian, faced with falling ad revenue, made a plea to its readers. Instead of putting up a paywall, which would go against the paper’s idea of a free and open internet, they asked for grassroots support in the form of voluntary memberships. It was the carrot to the paywall’s stick, and it worked. Since then, The Guardian has grown its paying membership to 300,000. Despite comprising less than 0.01% of the site’s 34.7 million monthly visitors, The Guardian’s revenue from members now exceeds that of advertising.

The Guardian’s plea for support. The company now earns more from reader donations than from advertising revenue

Grassroots support like this is becoming increasingly popular online. Fans routinely tip Youtubers and Twitchers using Patreon, and sites like Kickstarter and GoFundme allow users to crowdfund everything from new board games and watches to medical bills and political campaigns. Former employees of Gawker, bankrupt since losing a high-profile court case last year, are asking people to chip in for the media organization’s revival in a $500,000 Kickstarter campaign. If it succeeds, they claim, it will return as “an ownerless, advertiser-less, non-profit media organization”.

So we have reached a point where: a) an ad-blocker is a necessity for browsing the web securely, and b) a major news site can rely more on revenue from its readers than from advertising. Does this mean online advertising face a natural demise? Yes and no. At the very least, it is ripe for disruption. Advertising isn’t bad per se, it’s just been very badly implemented on the web so far. Rather than scrap online advertising entirely, it is the technology behind it that needs to be rethought. If the ad exchanges and data merchants are cut out of the deal, then perhaps a more equitable balance of privacy and profitability can be restored amongst users, publishers and marketers.

It might seem ironic then the man leading this effort to rethink adtech would be Brendan Eich, the inventor of Javascript. Without Javascript, online advertising would not exist. It is the only programming language that can run in your browser, so it’s the technology responsible for injecting ads and sending data back to ad exchanges.

Eich is spearheading the creation of Brave, a web browser with a focus on privacy and security. Brave’s major selling point to users is that it blocks ads and trackers by default. The project is a response to what Eich calls a “primal threat” to the web:

“I contend that the threat we face is ancient and, at bottom, human. Some call it advertising, others privacy. I view it as the Principal-Agent conflict of interest woven into the fabric of the Web.” - Brendan Eich

But instead of just being another piece of ad-blocking tech, Brave aims to reinvent the advertising model altogether to make a fairer deal for publishers and advertisers as well as users. The browser ships with Brave Payments, a wallet that lets users pay publishers as they browse, based on a voluntary monthly budget.

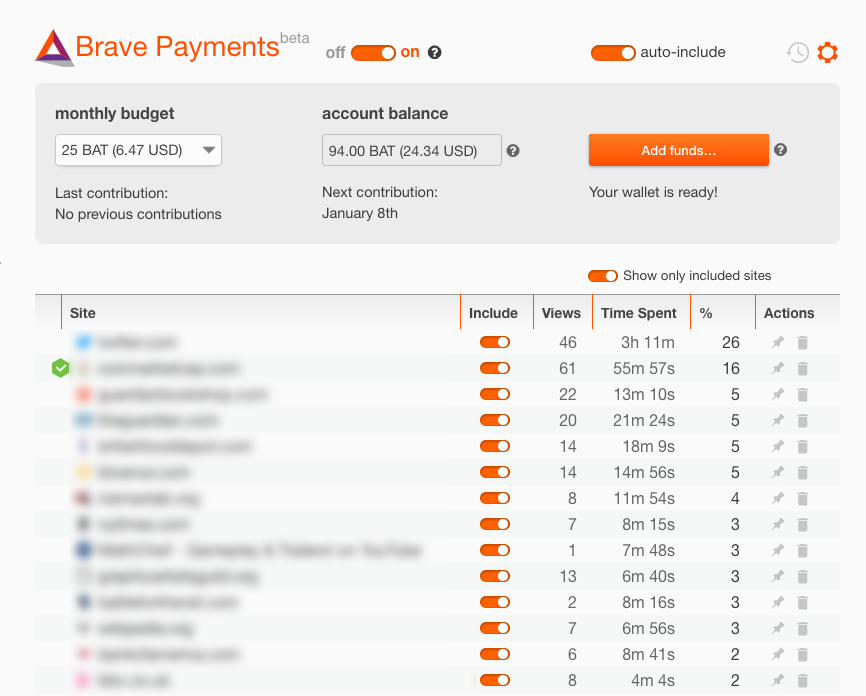

The Brave Payments wallet. Sites eligible to receive donations are listed in order of how much time the user has spent visiting them. A green checkmark indicates that site has signed up to receive payment

Brave users fund their wallet with a cryptocurrency called Basic Attention Token (BAT). The premise of BAT is that user attention has an intrinsic value that drives the digital economy. BAT aims to be a monetary representation of this attention, whether it is to editorial content, video, advertising, games, and so on. At the time of writing, 1 BAT is worth roughly 0.50 USD.

Once a Brave user has funded their wallet they decide how much money they are willing to donate to publishers every thirty days, from 25 to 100 BAT. Each payment cycle, BAT micro-donations are sent directly to publishers’ wallets, either at a fixed amount per month or based on the proportion of time the user has spent on that site relative to others.

The best thing about Brave’s payment model is that it doesn’t require publishers to make any binary decisions about how they want to be funded. Sites can continue to serve regular ads to non-Brave users and receive BAT from Brave users at the same time. In fact, BAT that has already been paid to publishers is currently held in escrow, meaning a site need only verify ownership of their website and set up a BAT wallet to receive all back-dated payments (unclaimed BAT will eventually be returned to the user growth pool to be distributed into the ecosystem by other means). If the Brave project is successful, ad revenue for publishers will gradually shift from dollar payments in traditional adtech to BAT from users and advertisers.

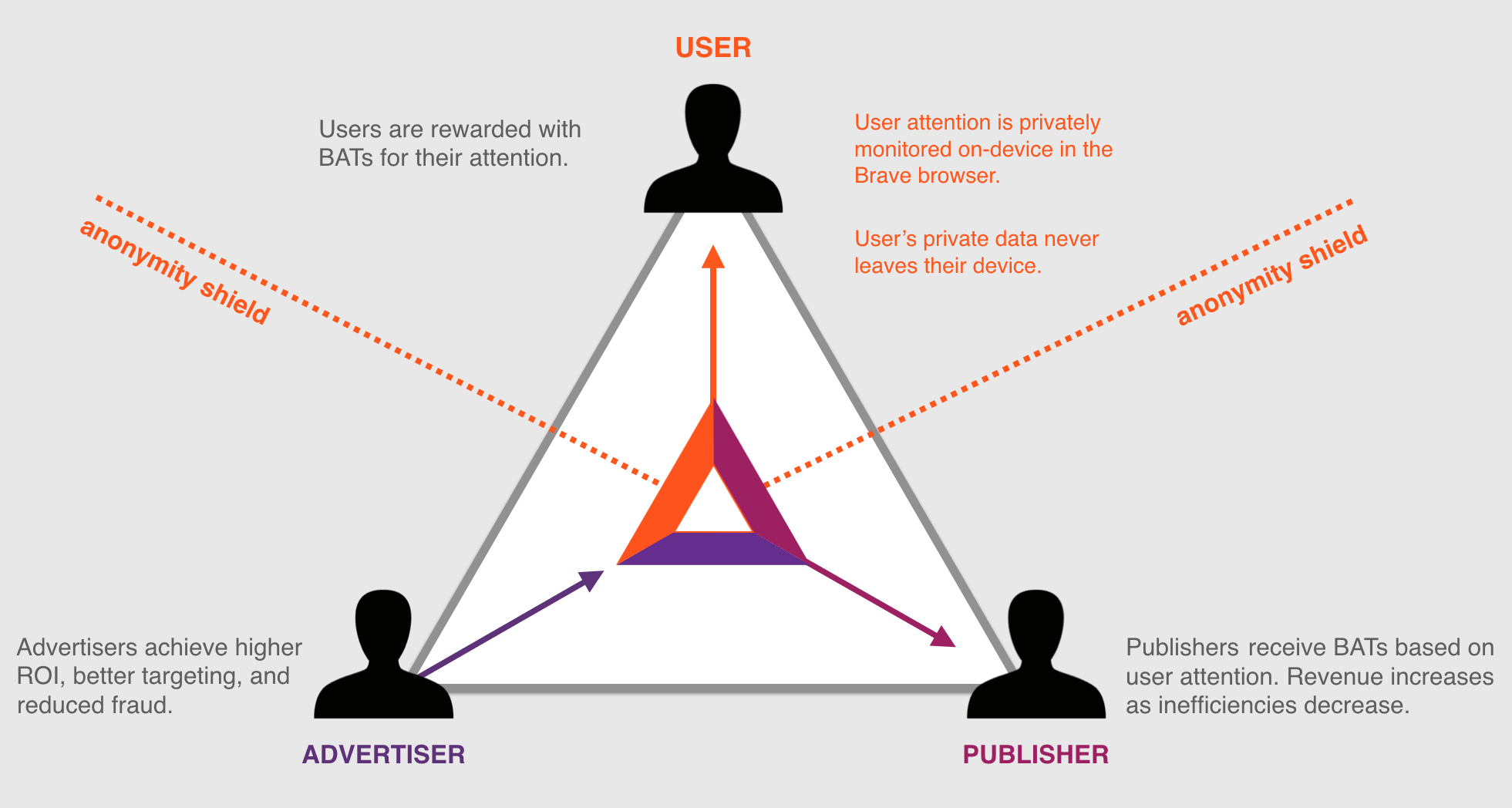

In phase two of Brave’s development roadmap, Brave users will be able to opt-in to seeing safe ads as they browse. The Brave wallet will then go from being unidirectional (currently you can only fund your wallet and pay publishers from it) to bi-directional, allowing advertisers to pay BAT to publishers for placing ads on their site and to users for viewing those ads. Using hypothetical numbers as an example, an advertiser would pay 1 BAT per impression of a banner ad, of which 0.15 BAT would be paid to the user and 0.7 BAT paid to the site it was loaded on (Brave will take the remaining cut as payment for their role in delivering the ad, so not all the middle men are cut out). Once the user has loaded ten pages containing this ad, they will have accrued 1.5 BAT, or around $0.75 at today’s conversion rates, in their Brave wallet. This credit would be automatically donated to publishers or content creators of the user’s choice via Brave Payments.

Whether or not a user chooses to see ads could be a useful toggle depending on context. The user could opt-in to seeing ads while she is browsing the web at home on a wifi connection and be paid BAT for each ad impression. Later, she could redeem those BAT in ad-free mobile browsing when she is out of the home and has limited battery power or data available.

The ads that Brave users can opt in to seeing will be different to the kind of ads we’re used to. Brave will use its own ad exchange, which will serve only carefully vetted, lightweight, UX-compliant, non-snooping ads. The ads will be served from a local ad cache, so there is no need for them to send any data remotely, nor will they rely on third party information about the user in order to serve ads in a relevant way. Since the user already trusts their browser, it is not a violation of privacy for the Brave ad exchange to use local data such as browsing history. Even analytics data about an ad’s impressions and click-through rates, metrics that are vital for advertisers in order to know the effectiveness of a campaign, will maintain the user’s anonymity through the user of zero-knowledge proofs.

The user/publisher/advertiser payment model on which BAT is based. From https://basicattentiontoken.org/

Because BAT is not tethered to Brave, it could have many applications outside of web browsing. If successful, we could see its use in on-demand streaming services or in video games, where BAT accrued by watching interstitial or in-game ads could be redeemed against subscription fees. It is this open-endedness that makes the project such an exciting prospect.

In many ways, BAT is the perfect use-case for a cryptocurrency. It is decentralized, allowing users, publishers and advertisers to pay each other directly without middle men. It is not tied to any particular country, so international payments aren’t an issue if you’re browsing content from another country. And as a publicly traded asset, its value in dollar-terms will be decided by a free market over time. This is important because in the current system, the dollar value of user attention is hard to calculate due to the sheer number of parties profiting from it. The value of the BAT will absorb these parities shares as they are gradually removed from the equation.

Although the BAT is traded on cryptocurrency exchanges, much of its current price is speculative– we won’t begin to understand the true dollar-value of a BAT until Brave’s ad-exchange is launched and the three-way user/advertiser/publisher triangle is complete. This value will be derived from myriad factors such as online publishing overheads, the monetary value that users ascribe to their time spent online, the cost of advertising and how it converts to revenue, and how highly users value privacy and reduced computing strain and battery use.

BAT sits at the convergence of a number of trends. For publishers, revenue from online advertising will continue to decline, in large part due to Google and Facebook’s dominance over worldwide ad spend (more than two-thirds of global ad spend growth from 2012 to 2016 came from those two companies). At the same time, revenue from member-supported payment models and voluntary donations will increase. Finally, the increasing invasiveness of ads will result in more and more browser and OS vendors protecting their users with increasingly strict blocking technology. In short, the online advertising world is changing fast, and Eich’s team is well placed to take advantage of that.

The goal of making BAT a store of worldwide user attention is certainly a lofty goal, but it’s plausible that it could at least capture a significant chunk of the digital advertising market. Here’s how I think that will happen:

- Brave’s user base will continue to grow organically as they release more features and users become better educated about the privacy concerns of current adtech.

- Brave will launch its ad exchange (some time in 2018), causing user interest to spike significantly, especially amongst cryptocurrency circles. The release of Brave ad-replacement browser extensions for Chrome and Firefox will also contribute to its popularity.

- As the number of users blocking ads via Brave or its extensions grows, so will the number of users making voluntary donations via Brave Payments. At the same time, BAT will increase in value against the dollar, giving publishers and content creators (like Youtubers and Twitch gamers) greater incentive to accept BAT payments.

- Once Brave owns a sufficient share of browsers and ad-blockers, advertisers will be forced to use Brave’s ad exchange or miss out on a highly valuable demographic of tech-savvy cryptocurrency nerds and early adopters.

- Eventually, Brave will own a large enough market share that more mainstream publishers and advertising brands will join in, although it’s likely that the biggest of them will hold out or even fight Brave for some time to come.

It’s going to be an interesting ride for Brave. There is certainly a need for better protecting users as they browse the web, and the rampant privacy violations of current adtech mean that something has to give. They will almost certainly face resistance from the giants of online advertising, and probably a fair amount from publishers who currently rely on them to keep the lights on.

Whether or not BAT is successful depends on two factors: the popularity of Brave and the success of cryptocurrencies as a concept. But Brave’s mission of increasing user privacy is a noble one, and it deserves to succeed.