Last summer my girlfriend and I spent a week in Iceland. We flew from Reykjavik to Akureyri and drove back via the Hringvegur - the ring road that encircles the island’s volcanic, inhospitable inner territory. Iceland is sparsely habited to a degree that makes it feel otherworldly, but is nonetheless a highly popular tourist destination. We were two of over 2 million tourists that visit Iceland each year - roughly six times the country’s population.

A small but highly visible form of tourism in Iceland is visiting by cruise ship. Enormous liners are a ubiquitous sight in ports around the country, where they dwarf the fishing vessels that until recent decades were the main engine of the Icelandic economy.

The numbers involved with modern cruise ships are almost meaninglessly big. The heaviest cruisers rival aircraft carriers and oil tankers in size, with construction costs often exceeding one billion dollars. Royal Caribbean’s Oasis class cruisers, currently the largest passenger ships in the world, are 360m long, weigh over 225,000 tons and can house over 5,500 passengers and 2,200 crew for weeks at a time. Each of the four active Oasis class ships is bigger, heavier and more capacious than the Chrysler Building.

Despite this heft, many of these vessels are remarkably maneuverable. Most large cruise ships have a draft of less than 9m and are equipped with 360 degree azimuthing propellor pods which afford them a narrow turning circle. Like the Viking longboat, they can sail far up rivers and fjords, offloading their passengers right into the hearts of cities and towns in the farthest corners of the world.

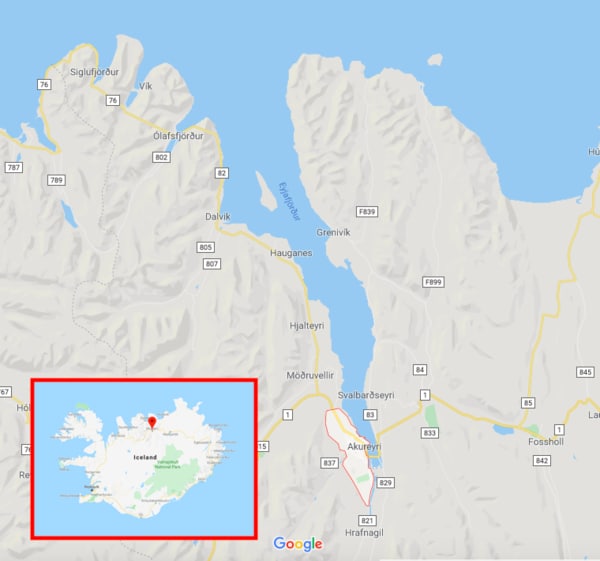

For most of our Icelandic visit we stayed in Akureyri, the country’s second ‘city’, a relative term in Iceland - with a population of just 20,000 people it would be classified as a medium-sized town in the US. Akureyri is built on a hillside at the inland-most point of a fjord called the Eyjafjörður, and most mornings during the summer months a cruise ship sails the 60km from the mouth of the fjord in the north down to the port in Akureyri, where it sits and waits for its passengers, anywhere from a few hundred to several thousand, to look around the town before sailing back out to sea that evening. Armed with a pair of binoculars and the MarineTraffic app on my phone, I would identify each day’s visiting ship and compare it to the last, boring my girlfriend with statistics and itineraries while we ate our morning skyr and berries.

One morning I looked out of our vacation apartment window to see the Disney Magic in port, owned and operated by Disney Cruise Lines (DCL). Magic is relatively small for a modern cruise ship at 86,000 tons (the following day’s visitor would be the MSC Preziosa at 139,000 tons), but it had an outsized presence in the port thanks to the exhaustive efforts of the Disney marketing department in the ship’s livery, which included red and blue Mickey-mouse themed paintwork and giant Disney logo emblazoned on each funnel.

Maritime etiquette dictates that visiting ships fly the flag of the host port’s country as a sign of respect, but the Icelandic cross was absent from the bow of the Magic, which instead flew its own flag bearing the Mickey Mouse head silhouette. Even the ship’s twenty lifeboats matched the bright yellow of Mickey’s bow-tie and shoes, DCL having successfully petitioned the UN International Maritime Organization in the nineties to permit a lifeboat color that deviated from the regulation dayglo orange.

The ship’s passengers were not exempt from carrying the Disney brand, their matching t-shirts a recurrent visual theme as they were bussed around the town on chartered coaches during their brief on-shore visit. Despite being tourists ourselves we felt a greater kinship with the local residents, the subjects of a sightseeing excursion by visitors curious of their surroundings but reluctant to integrate with them.

In the evening the Magic blasted its horn, a seven-tone ditty to the tune of When you wish upon a star, which echoed around the hills surrounding the Eyjafjörður. Gradually the Disney cruisers headed back to eat their dinner aboard the ship as it prepared to return to sea.

The Eyjafjörður fjord with Disney Magic docked in Akureyri port

Cruising has always struck me as an odd choice of vacation, a bit like staying in a hotel for a week and only venturing outside for a few hours every other day. It’s a vacation that bears closer resemblance to a theme park than the vacation we were on. On a DCL cruise, Akureyri and other port stops are not so much destinations as backdrops to the Disney experience, artificial locations like Disneyland itself. See gothic German castles like the one in Tangled, or snow-swept Scandinavian vistas like the ones in Frozen, while Elsa and Anna sing to your kids. Why invite the world to Disneyland when you can take Disneyland to the world?

Hosting these ships is the cost of doing business in a country whose economy relies heavily on tourism, but it must be a tough sell. The cruise industry as a whole has an appalling track record on environmental impact (see: Venice) and its massive vessels dominate small coastal towns while keeping passengers on the ship as much as possible. Accommodation, travel and food are already catered for onboard, leaving scant profit to be made by the local economy. They are the new longboats, sailing inland not to rape and pillage but to give their passengers nice photo opportunities and to leave the local residents inadvertently humming When you wish upon a star for days afterwards. It’s a more profitable enterprise than their Viking ancestors could have dreamt of.

That night, unable to sleep as the midnight sun peeped through the blinds of our room, I unlocked my phone and opened MarineTraffic to see where the Magic was on the map. It had reached the Greenland Sea and was en route to its next port call in Kirkwall, Scotland, another former Viking settlement in the Orkney Islands at the northernmost tip of the UK. Its population: 9,293.